Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

![Nervous Conditions [Import]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41sYcrUCFNL.jpg)

📖 Unlock the power of perspective with Nervous Conditions — where every page challenges the status quo.

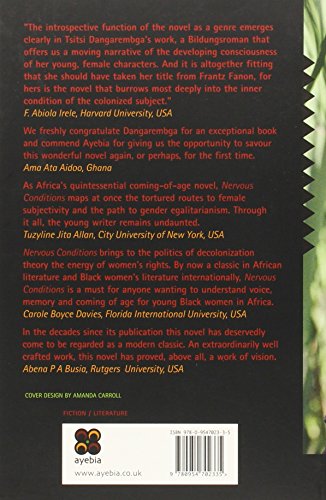

Nervous Conditions by Tsitsi Dangarembga is a critically acclaimed coming-of-age novel that explores the complexities of colonialism, gender, and social mobility in Zimbabwe. This import edition, ranked among the top in its genre, offers a compelling narrative through deeply nuanced characters and themes that resonate with readers seeking to understand identity and systemic oppression. A must-read for those interested in postcolonial literature and the African diaspora experience.

| Best Sellers Rank | #578,432 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #552 in Coming of Age Fiction (Books) #1,988 in Literary Fiction (Books) #10,418 in Contemporary Women Fiction |

| Book 1 of 3 | Nervous Conditions |

| Customer Reviews | 4.5 4.5 out of 5 stars (1,930) |

| Dimensions | 5 x 0.75 x 7.5 inches |

| Edition | 2nd |

| ISBN-10 | 0954702336 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0954702335 |

| Item Weight | 7.2 ounces |

| Language | English |

| Print length | 224 pages |

| Publication date | December 19, 2004 |

| Publisher | Ayebia Clarke Publishing |

R**E

Excellent Detail on the Violence of Colonization

An engaging (and fast) read. A must read for any one in the African diaspora experiencing some kind of change in social class (e.g. being first in the family to attend college or graduate school) or otherwise having suspicions about the sources of their feelings of alienation. Specifically, this is an amazingly relevant depiction of the pain experienced by those who do as they're told and pursue education to "better themselves": the richness of this book's characters show just how many costs go unstated by those who have the privilege of not paying said costs and unacknowledged by those who haven't had to go through the violent process of being harshly disciplined into being acceptable by the dominant segments of society. Nyasha's character resonated most with me: I, too, feel frustrated by what seems to be an obvious oppressive reality around me as well as the extreme deprivation that can encourage oppressed people to appear complicit. Additionally, most of the other characters also helped open my eyes to the ways that I have failed to understand why people with situations different from my own can seem complicit in their own subordination. The discussion of how gender plays out also may be eye-opening for those with little clarity on the violence that seeming innocuous hierarchies produce (e.g. even "good" people can enact said violence). I plan on reading the sequel, although I've heard it's not as good. I also recommend this book to: -Any person who doesn't understand the severity of the violence of colonization on those who have been colonized (e.g. people who aren't part of a colonized group, people who firmly believe today's racism is "less bad" than yesterday's) -Those who don't see why people in the African diaspora are often concerned with what often is written off as mere "identity politics" (as opposed to a legitimate sense of loss) -Any person who is having a hard time understanding how "nice" and "good" people are still among the hands that enact violence against colonized peoples -Any person who is having a hard time understanding how a "minority" can be among the hands that enact violence against (their own) colonized people (e.g. people who firmly believe in a rigid category of "sell-outs")

J**I

I liked a lot of it…

It’s hard for me to rate this book because on the one hand, I really resonated with this story and the characters and as an African, it was a story told with a lot of heart and nuance and reflexivity. We get the benefit of Tambu’s older self editorially providing wisdom and reflection as she looks back at her younger self. And this is helpful in casting Tambu as a sympathetic character because with time and with age, there’s clearly been a lot of analyses of how she sees things. But despite her promising start in this story, I couldn’t help but feel that she wasn’t really the main character in her own narration. The premise is that when Tambu loses her brother, who happens to be her nemesis, she inherits his opportunity to move in with their wealthy uncle to pursue her dream of an education and a better life for her family. But she finds that life isn’t as perfect as she believed in the household of her god-like uncle and aunt, and she finds that in the pursuit of her dreams, she may be losing her identity. This was set up like it was going to be Tambu’s coming of age story, but it didn’t really deliver on that expectation. In the end, it was kind of a collection of incidents and events about family expectations, gender inequity and coloniality and the legacies of compromising oneself for the Western gaze in order to be successful enough to look after one’s family. Yet even though my expectation for a connected story about Tambu wasn’t met, and even though this was very “slice of life,” I think it articulated experiences that were very realistic and pertinent to a Zimbabwean and more broadly, African, experience. The character development was stellar, the scenes and reflections were on point, the scenarios and ways of thinking resonated. I could see the experiences of my own family, friends and neighbours in the grievances and hurts and expectations and hopes and responsibilities that lay in this book. I loved the complex family dynamics and the imperfect characters. If I’m removing one star, it’s because this did not feel entirely cohesive to me. I enjoyed the stories but I did feel it felt a little incomplete and “so what” at the end. It left me as a reader wondering what the author wanted to accomplish with this story which ended as abruptly as it started, kind of in the middle. I also thought it was a strange choice to include a spoiler-ridden introduction at the start of this edition. My understanding is that this is the first book in a trilogy of books featuring Tambu which might explain why this is so abrupt but I also felt like this didn’t end on a cliffhanger or with any express trigger to pick up the next book. I really liked the story and would like to see what older Tambu’s foreshadowing will lead to, so I plan to check out the other books in the series. I recommend.

M**I

Ho dato 5 stelle a questo libro perchè oltre ad avere un'ottima presentazione generale risulta leggero, maneggevole e ordinato nella formattazione. Ottimo e completo di epigrafe, introduzione e note che permettono, per chi come me studia all'università, di avere un quadro completo sulle tematiche affrontate e quindi di approfondire gli studi.

I**S

This edition of Tsitsi Dangarembga’s novel has an introduction by Kwame Anthony Appiah that was written twenty years ago and sixteen years after the novel was first published in the UK. In many ways not much has changed since 1988 or 2004 in terms of gender. And maybe not since the novel’s setting in the Sixties and early Seventies. In fact, maybe we’re going backwards. Kwame Appiah’s introduction begins with the first words of the novel proper: “I was not sorry when my brother died.” Those words are written by a woman of indeterminate age remembering the day her brother failed to come home for the holidays from his mission school. The narrator, Tambu, was around thirteen at the time, her brother Nhamo a year older. We learn that they lived in what was then Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. Theirs is a family of subsistence farmers who are not quite dirt poor as they have a reasonably sized house with some furniture. Two reasons they’re not on the breadline – despite the laziness of their feckless father Jeremiah – are the industriousness of Tambu’s mother and the benevolence of her uncle, Babamukuru. He is headmaster of the mission school in a nearby town and he and his wife Maiguru have had the good fortune to go to university in South Africa and England. He lives in a big house, has servants and two cars and he takes Nhamo under his wing. The plan is that the boy will benefit from a good education and raise his side of the family further up the social ladder. Despite the value that many characters – including Tambu – place on education, there is a strong feeling that it is wasted on males and females in different ways. Babamukuru has had access to “western” ideas, having spent five years in England in the Swinging Sixties doing a Masters. However, he has still come home as a patriarch with traditional ideas about hierarchy and a “woman’s place”. His wife Maiguru is also a post-graduate but she has had little opportunity to use her education, apart from doing some teaching at the mission school. She is a submissive wife who humours her husband and rarely challenges his authority. Nhamo as a teenage boy appears to be following Babamukuru’s example. He has been doing well at school but he uses his male privilege to lord it over Tambu and remind her that as a girl she is his social and intellectual inferior. He is lazy and selfish and refuses to help on the farm when he comes home for the holidays. Meanwhile Tambu often has to miss classes at the local school to milk the cows or because there is no money to pay the fees. Being the resourceful type, at the age of about eight she starts growing maize to sell in the local town to pay the school fees. She gets not support from her family for this, including her mother, who is suspicious of education. Neither of her parents believe that girls need any education beyond cooking and chores around the farm. Then Tambu’s brother dies suddenly of mumps. His death opens doors for Tambu because her uncle decides that she must replace Nhamo as her family’s hope for the future. This puts her in closer touch with her cousin Nyasha. You think this is going to be a wonderful, rich friendship but it’s problematic. Nyasha is about the same age as Tambu, but she has spent five years in England with her parents and has come back with a head full of western traits (we see her reading Lady Chatterley’s Lover) and a miniskirt. Tambu still shares her family’s traditional ideas so she finds Nyasha’s version of Sixties permissiveness (short skirts, smoking, hanging out with boys) rather shocking. However, they share a room and after some initial mutual suspicion, they do become friends. Nyasha can’t reconcile her experience of life in England and her intellectual curiosity with the straitjacket that traditional norms impose on her and she develops bulimia. This is her protest against paternal authority and the injunction for women to give men curves. Which reminds me that the novel has another admirable female character, her mother’s sister, Lucia. She likes having sex with men and although this has disadvantages for her – she gets pregnant by a deadbeat – she has enough spirit to flick the finger at anyone who sneers at her. She also has enough brains to get her way. She persuades Babamukuru to give her a cooking job at the mission school, which enables her to go to evening classes. A better future awaits her. I won’t say what becomes of Tambu, but there is hope at the end of the novel that a better future awaits her too. I will definitely read more books by Tsitsi Dangarembga.

N**S

Am happy

D**N

It is my first book by any Zimbabwean writer. Tambudszai is thirteen and lives with poor parents, an elder brother, and two little sisters in an unknown village in Zimbabwe. To uplift the family fortune, her father's elder brother, a headmaster in an English missionary school, takes her brother, Nhamo, to the mission and sponsors his lodging and studies. But when he died due to a strange illness, his position was taken over by Tambudszai, an ambitious, confident, focused, revolting, yet disciplined young lady. The author excellently portrayed the social, financial and psychological endeavour journey of a young, poor, and deprived rural girl in patriarchal colonial Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, in the 1970s. Dr Brij Mohan Author-Second Innings.

S**L

Different

Trustpilot

2 months ago

1 month ago