Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

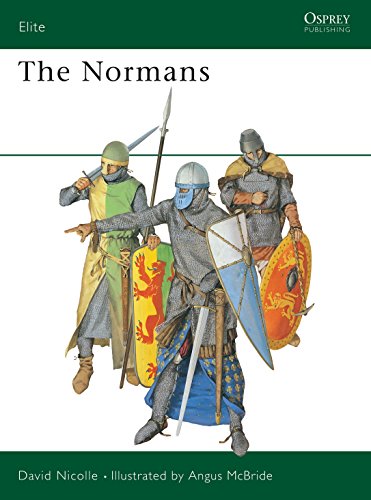

The Normans: No. 9 (Elite)

J**S

Superb plates, uneven and sometimes outdated text

This title was first published in 1987 and while it remains mostly good as an overview and a general introduction to the Normans, it shows its age and contains a number of inaccuracies and questionable statements. However, most of the main points are nevertheless made and the largely superb plates from Angus McBride help mitigate at least some of these limitations.First, David Nicolle’s text is at times outdated. This is particularly the case at the beginning of the book, in the first section dealing with “the Norman Legacy” where the simplistic opposition between “tamed Vikings” or “provincial Frenchmen” is almost a caricature. They also reflect debates that are over thirty years old and these are somewhat obsolete given the numerous publications that have taken place on Norman identity.A similar point can be made about the importance of the Normans in British and European history, with the author stating that it “is denigrated or at least accepted only grudgingly, be the English-speaking world.” This was true up to the early eighties and reflected “pro-Saxon” views going back to Victorian times, but historians’ perspectives have largely changed since then, including those of British historians (see the works of Marjorie Chibnall or David Bates, just to mention these two, among many others).Then there are some inaccuracies, omissions and questionable statements. I was very surprised to learn that, according to the author, the first Normans “arrived probably as armoured infantry” in Ireland. On the contrary, they arrived with their horses and it is this heavy cavalry that allowed them to gain the upper hand despite their small numbers.Also, the statement that the majority of the population of the Byzantine province of Langobardia (roughly modern Apulia in Southern Italy) was “Italian” with the exception of Greek-speaking inhabitants around Otranto is simply anachronistic. There was no such thing as an “Italian” during the 11th century. Instead, they seem to have been mostly Lombards, with a number of other minorities settled in the major ports during Byzantine rule (such as an Armenian community in Bari, for instance).There are about a dozen other strange and questionable statements across the book. One of these states that “the principality of Antioch was never able to fully establish itself in the mosaic of Middle Eastern states”. The exact meaning of this statement is unclear. A similar statement could also be made for any of the other Crusader States to the extent that their existence was threatened and depended upon the links and reinforcements coming from the West. In the case of Antioch, it also depended upon keeping good relations with the large Armenian populations within the principality and to the North of it, and, up to 1180, on avoiding antagonising the Byzantine Empire.In a second, even stranger, statement, David Nicolle comments that the Norman military elite were not “able to integrate themselves into Syrian society.” This, however, largely misses the point. First, one could wonder whether there was such a thing as a “Syrian society”, with this expression implying some sort of unity or common culture that is at odds with the previously mentioned “mosaic of Middle Eastern States”, some of which were Latin, while others were Arminian, Byzantine, Sunnite or Shiites (the Assassins). Second, the “Franks” were always a minority in all of the Crusader States, an d they remained so, even in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, throughout the existence of Outremer. Third, there is hardly any mention of “Normans”, whether knights or not, after the middle of the 12th century in the sources, simply because they did “integrate” and became largely indistinguishable from other Franks. Fourth, the fact that five more Princes of Antioch were names Bohemond after the death of Count Bohemond’s son in 1130 (Bohemond II) shows a sense of dynastic continuity but this does not allow the author to conclude that “feelings of Normanitas nevertheless remained strong in Antioch.”Having mentioned these flaws and illustrated them through a few examples, it is also fair to mention that David Nicolle does make most of the main points.One of these is the Normans’ adaptability, although, contrary to the author, I am not at all sure that it is this that “set them apart from the Vikings” since these exhibited something similar whether in Russia, in the Hebrides or in Ireland. Another point, related to the previous one, but that the author could have emphasised more is that virtually all of the so-called “Norman armies” were in fact heterogeneous forces, with Normans from Normandy only making up a portion of the total force. Even at the battle of Hastings, the “Normans” could have made up no more than half the army, alongside numerous Flemish and Bretons, but also warriors (both cavalry and infantry) from Maine, Anjou and even as far away as Burgundy. This was even more the case for the Normans in South Italy and Sicily where Lombards, Greeks and other Frankish knights (plus Muslims in Sicily) made up most of their forces.Then there are the rather gorgeous plates. One, is particular (plate I describing the Normans in the East), is perhaps my personal favourites. It shows two Normans, one as an ex-byzantine mercenary and the other as an Italo-Norman Crusader, with the third character being Oshin the Hethoumian, one of several Armenian officers serving in the Byzantine Army who continued to hold against the Turks the provinces and fortresses where they had been stationed well after most of Asia Minor had been lost to the Byzantines. One of the most interesting is the armours of the two milites as they tend to complement their mail shirts with borrowed bits and pieces, whether the (byzantine) scale leather armour or lamellar armour. Both are worn on top of the mail shirt, probably to offer better protection against arrows from horse archers. The illustration of the two knights is derived from the carvings of a Church in Southern Italy.However, and contrary to David Nicolle’s assertion, it is somewhat unlikely that the lamellar armour comes from Sicily. It certainly does reflect Moslem influence, but this is much more likely to the Turkish since lamellar armour reflected Turkish-Iranian influences. The point here is that rather reflecting the kind of equipment with which these knights might have left Southern Italy for the East, the carvings, done to commemorate their deeds, are much more likely to reflect the kind of armour they might have been wearing on their return.Three and a half stars, rounded down to three stars.

S**L

Norman’s Rock

Not much I can add to this. It’s up to the normal Osprey standard and I have many many of them. I always consider Osprey as a starting place for further research. And have been collecting them since the 70s. Won’t hear anything bad said about them.

M**R

A first class introduction to the Normans

The Normans are a much underrated race, especially in the Anglo-centrist world. For a brief flowering of 200 years, Normans rules kingdoms from Normandy,the Levant, Sicily to England. The economic and military powerhouse of Europe.David Nicolle is to be congratulated for squeezing all of this into just 40 pages. If all you want is a taster to a vast subject, this is a five star offering..

A**R

good price

not read yet but I enjoy everything Viking norman saxon happy with order

L**E

medievil

this was a gift to my brother in lawdid not read it myself

Trustpilot

3 weeks ago

1 month ago