Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

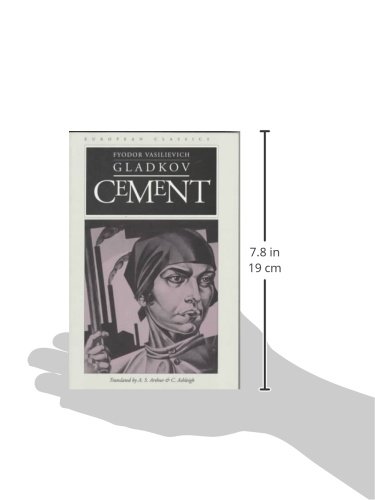

Cement (European Classics)

J**T

The Prose of the Unfree

Did you know that the communists invented an entirely new genre for literature? When people talk about ‘Socialist Realism’ they most often think of the paintings of Diego Rivera like “Man at the Crossroads”, the heroic laborer seizing fearlessly the levers of industrial machines – the noble farmer toiling the fields. Tractors of the world unite!!! Scenes of Stalin receiving flowers from a group of ruddy little children from the Ural mountains. Pristine soviet villages sharing milk and honey.But the soviets also used the written word – socialist realism in novels. Adopted officially in 1934 by the party and ratified by Stalin, this new genre “…demanded that all art must depict some aspect of man’s struggle toward socialist progress for a better life. It stressed the need for the creative artist to serve the proletariat by being realistic, optimistic and heroic.”“Cement” by Fyodor Vasilievich Gladkov was one of the first and perhaps the blueprint for the genre. The story depicts the struggle of a village post-revolution to restart the cement factory in their midst, which has gone silent after the original managers were killed. In true socialist realism style, it ends on a high note; with a hero and a victory. But nevertheless I was surprised by the story, because it was not a story of nobility and loss and dignity against the odds. It was instead a tale of intrigue, petty infighting of the new communist overlords, exclusion, suffering and sadness. This book was tremendously sad. I suppose the point was to instill the need for sacrifice, to remind people that it would not be easy. To find that delicate balance between an ideology which can never be made to function as a model of government and the hopes that with only a little more work something will go right – though it never does.One thing did surprise me, “Cement” was extremely well written. I who have read much Russian prose (as I’m sure you have) have accepted the fact that reading Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Solzhenitsyn, Chernyshevsky is a slog. A dreadful march through pages and pages of dialogue that seem to go nowhere, long-winded descriptions of incidents and places that are tangential to the stories. But not Cement, which was in fact a relatively easy read and in some places exhibited real rhetorical flourish.“Without understanding why, Gleb felt wings unfolding in his soul. All this, the mountains, the sea, the factory, the town and the boundless distances beyond the horizon – the whole of Russia, we ourselves. All this immensity – the mountains, the factory, the distances – all were singing in their depths the song of our mighty labour. Do not our hands tremble at the thought of our back-breaking task, a task for giants? Will not our hearts burst with the tide of our blood? This is Workers’ Russia; this is us; the new world of which mankind has dreamed throughout the centuries. This is the beginning: the first indrawn breath before the first blow. It is. It will be. The thunder roars.”It is so sad to see such talent put to the service of such a tremendous evil as was communism. I wonder what an amazing world Gladkov could have helped build, if he’d only been free.

R**L

Paradigm of Socialist Realism

In Cement, a classic of socialist realism and an exemplar of the production novel, Fyodor Gladkov portrays the sociological effects of Communism on the inhabitants of a mountain town after the Russian Revolution as they attempt to rebuild their lives under the new economic policies of the Soviet Union. Written to a master plot that controls the most critical elements of the story, the novel illustrates major tenets of Soviet ideology. Task fulfillment is combined with the maturation of the positive hero as he transcends his selfish interests and finds self-fulfillment in the collective cause of Communism. Gleb Chumalov, having distinguished himself in Civil War battles, returns home to discover things have changed dramatically. The cement factory is idle, petit bourgeois values remain, and the local officials are not committed to a reopening of the factory. Moreover, his wife, Dasha, is now the leader of the local Women's Section of the Communist Party, and has no interest in continuing their marriage. Chumalov perceives that the battle for communist survival must now be fought on the economic front and he redirects his energies to accomplish this task. Overcoming worker apathy, red tape, and sabotage, Chumalov mobilizes the proletariat, challenges the bureaucrats, and succeeds in achieving the reopening of the factory on the fourth anniversary of the October Revolution. In a speech marking the completion of the task, Chumalov envisions a wonderful life for future generations under communism. In further development of the motif that sacrifice will lead to a common good, Serge contemplates life after his purge from the Communist Party because of his Menshevik ties: " he, Serge Ivagin, as a personality did not exist. There was only the Party and he was an insignificant item in this great organism."[1]Katerina Clark suggests that although Cement, in many ways, exemplifies the prototypical Soviet production novel, largely due to the fact that its plot and positive heroes were imitated more than any other in Soviet fiction, especially in the 1940s when Gladkov was director of the Literary Institute, it is better viewed as an embryonic form of such novels. She concedes that Cement, written in 1925 before Stalin's rise to power, did indeed include much Pravda rhetoric, especially the theme that the fight for communist survival must be redirected to the economic front. She argues, however, that unlike the conventional socialist realist novel, Gladkov uses language and imagery of several nonpartisan highbrow literary schools of thought. Gladkov's opulent prose was repeatedly criticized, and he rewrote the novel several times in response to his critics. Notwithstanding the alterations, the hero image he projected in Gleb Chumalov remained in tact, and became a convention for later Soviet realist novels. In Clark's view, Cement demonstrates that Stalinist culture was influenced by a variety of preexisting elements and was not something that was handed down solely by the dictator himself.[2][1] Fyodor Vasilievich Gladkov. Cement. Evanston: Northwestern UP, 1994, 296.[2] Katerina Clark. The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2000.

J**A

Socialist. Realism

I first came across Cement because I was looking to read something that was representative of socialist realism. And this book was held up as perhaps the best exemplar of that genre.It is the story of a man who comes back to his hometown after the Russian Revolution fighting in the Army and he finds that everything has changed. The social structure has changed. His wife has changed. And he and the rest of the village must come together and get a cement factory back up and running. They must fight not just local reactionaries but also the bureaucracy of the Soviet system.As story in the translation, it's not that bad, but it is more of interest as a historical text than it is just a fun book you're going to sit and read. The other thing of note is that it makes me think of the contemporaries of this text. It was written in the twenties and at the same time Mikhail Bulgakov was writing Master and Margarita and Heart of a Dog -- much more interesting modernism influenced text than this is. So at least that time artistically you were able to have a very separate threads representative in Soviet literature. Overall, I would say it is worth a read but again as the representative text of the genre.

M**I

good prevails.

Life in post-revolutionary Russia was no picnic with mass starvation and lawlessness. This book focuses on a guy who is trying to get the cement factory working again but finds himself fighting one committee after another and their role seems to be only to throw up roadblocks. There is much sadness but in the end, good prevails.

C**N

Cement - socialist novel

Cement - one of the first socialist realist novels from the early 1920s. A rip roaring roller coaster of a read. War, civil war, sexual liberation, liberation of the mind, understanding the real role of work, famine, tragedy - blows all the dust out of sentimental bourgeois literature. Wonderful!

Trustpilot

1 month ago

1 month ago