Full description not available

T**O

A Great book of Ancient Comedy

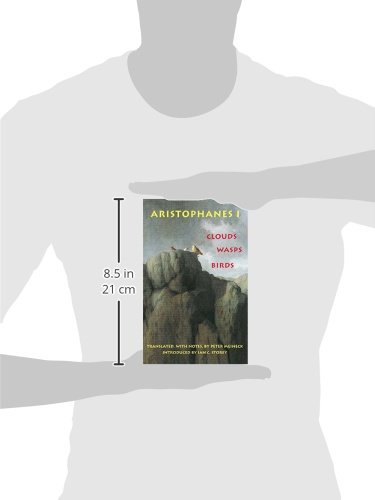

Clouds Waps Birds is a collection of 3 stories written by the Ancient Greek poet and writer, Aristophanes. Clouds is the first story, and it recounts the woes of Strepsiades, who worries about paying his debts. He hatches a plan and enroll his son Phillipides in "The thinkery" a place for people to learn to argue and debate, and he seeks to use his son to fend away his creditors in court. Phillipides refuses to enter the thinkery, and so Strepsiades enters himself. He begins to learn from Socrates. He begins to lose his morals in the pursuit of beign able to win any argument he finds himself in. Soon he does get his son to enroll in the school, and his son learns to debate too, and becomes the nerdy intellectual he was afraid of becoming in the beginning. When the first creditors come to Strepsiades house, he tactically defeats them himself, all with no morals or dignity, but all by argument. But when his own son Phillipides violently beats him, he finds he cannot out argue his son, who "proves" that it is right for a son to beat his father. He blames this on the Thinkery, and in dismay, takes his slaves and attacks the school. Wasps tells the story of two slaves awho are keeping guard over a "monster" in a house. The father of the house has a strange disease, he is addicted to law court. All medical attempts have failed, and he continues to progress in his problem. He continues to try to escape the house, even through the chimney, but fails. Then the man's friends try to free him, but at the end of the fight, he is still barely in custody. They agree to have a debate between the fater and his son, who seeks to keep him. The son is winning the debate, but the father doesnt give in, so they turn the house into a courtroom in compromise. Then the son continually fools the father into doing good, and is praised for standing up to monsters like his father Birds tells the story of two middle aged men who are looking for the "hoopoe", a large mystical bird. When they find him, they convince the Birdland that they rule the Earth and should build a city to stand up to the Gods. The birds agree, and begin building and making laws. Once the city is finished, however, several Gods sneak into the city, and people begin to try to come there as well. Then Zeus sends a delegation to the city, and Pisthareus sends all comers packing. Finally after dismataling the delegation of Zeus, Pisthareus is hailed as a hero and is proclaimed a God and receives the scepter of Zeus. The book is about 420 pages long, and is well translated by Peter Meineck, making it easy to read and understand. It is a great read for anyone interested in old Greek comedy, and is a wonderful read for anyone.It makes great use of prose, and poetry, and rhyme, and also has good humor. This a book by an ancient classic writer, and lives up to such expectations.

L**O

Three early Greek comedies by Aristophanes

"Aristophanes I" brings together three of the Greek comedians earliest extant comedies. The legend is that when Aristophanes' comedy "The Clouds" was first performed in Athens in 423 B.C., his target, Socrates, stood throughout the performance so that everyone in the audience was aware that he was there and hearing what was said of him. The portrait of Socrates clearly satirical and most critics consider it to be inaccurate. But Aristophanes is making fun of Athens' renowned "Think-tank" the "Phrontisterion," the school where the rich young men of Athens were taught the fine art of rhetoric. Instead of anything lofty the comic poet suggests the primary purpose of such an education is to be clever and out-reason greedy creditors. This is an especially good translation of the play, which includes insightful notes and essays on both Old Comedy and the Theater of Dionysus that helps readers understand the conventions of staged comedy at the time of Aristophanes. In this comedy Socrates is consulted by an old rogue, Strepsiades (sometimes translated as "Twisterson"), who is upset with the mountain of debts his playboy son Phidippides, who loves fast horses and fast living. Phidippides agrees to go to Socrates' school of logic where he can learn to make a wrong argument sound right. After graduation is able to use the system of "unjust logic" to outwit his father and kick him out of the family home. The Chorus of Clouds comments on the proceedings and in the end the Phrontisterion is burned to the ground by Strepsiades. The flaw of the play is Aristophanes is trying to satirize the Sophists, who were popularizing a new philosophy that denied the possibility of ever reaching objective truth, he picked the wrong target. The Sophists were mostly teachers who were not native to Athens, such as Isocartes and Gorgias. "Sophist" basically meant teacher, so while Socrates was a "sophist" he was not a "Sophist." Twenty-four years later, when Socrates was condemned to death for "corrupting the youth of Athens," the only accuser he said he could name was a certain "comic poet" who renamed nameless. The version of "The Clouds" that has passed down to us is not the original version, which was defeated by Cratinus' "Wine Flask" at a comedy competition during the Great Dionysia celebrations. We know this is a revised version because the Chorus complains about Aristophanes finishing third in that competition. However, critics assume it is essentially the same play, albeit a more polished version. Once you forgive Aristophanes for his unfair characterization of Socrates, "The Clouds" is a great comedy employing all of his standard tricks of the trade from fantasy and ribaldry to funny songs and obscene words. "Wasps" ("Sphekes") appeals to contemporary audiences because it satirizes the litigiousness of the Athenians. Actually, the play, produced in 422 B.C., is more about the permanent tensions between conservative and liberal politics. Aristophanes is attacking the practice of the politician Cleon's exploitation of the large subsidized juries used in by the Athenian legal system. Bdelcylen ("Cleon-hater"), representing the position of the playwright, maintains that pay for public service is the device of demagogues to purchase loyalty. His father Philocleon("Cleon-lover"), a mean and waspish old man who has a passion for serving on juries, represents the Athenians. Bdelcylen arranges for a court to be held at home to hear Philocleon's stupid little case of accusing the dog of the house of stealing cheese. The old man is cured of his passion for juries, becoming a drunkard instead. The best scenes in "Wasps" are Philocleon's attempts to escape when Bdelcyclen locks him up and the scene where the poor dog is tried. Certainly this play is representative of Aristophanes as a reformer, who wanted to persuade his audiences to change their foolish ways by ridiculing them on stage. The problem with "The Birds" ("Ornithes") is that for once Aristophanes does not seem to be attacking some specific abuse in Athens. Still, we suspect that even this little fantasy is not simply escapist entertainment. Certainly there are those who see it as a political satire about the imperialistic dreams that resulted in the disastrous invasion of Sicily (which happened the year before his play was produced in 414 B.C.). Then again, this could just be Aristophanes bemoaning the decline of Athens. Pisthetaerus ("Trusting") and Euelpides ("Hopeful") have grown tired of life in Athens and decide to build a utopia in the sky with the help of the birds, which they will name Necphelococcygia (which translates roughly as "Cloud Cuckoo Land"). Pisthetaerus and his feathered friends have to fight off those unworthy humans, malefactors and public nuisances all, who try and join their utopia. Then there are the gods, who come to make some sort of agreement with the new city because they have created a bottleneck for sacrifices coming from earth. Because it is a more general satire, "The Birds" tends to work better with younger audiences than most comedies by Aristophanes. Besides, the chorus of birds lends itself to fantastic costumes, which is always a plus with young theater goers. In studying any of the Greek plays that remain it is important to I have always maintained that in studying Greek plays you want to know the dramatic conventions of these plays like the distinction between episodes and stasimons (scenes and songs), the "agon" (a formal debate on the crucial issue of the play), and the "parabasis" (in which the Chorus partially abandons its dramatic role and addresses the audience directly). Understanding these really enhances your enjoyment of the play.

F**L

Five Stars

Great plays, well packaged.

C**N

Five Stars

An excellent translation with a very helpful introduction and notes to the text. I would recommend it.

Trustpilot

1 day ago

2 weeks ago